The Lonely Spirit

November 18, 2018 – March 24, 2019

Inside-Out Art Museum, No.50 Xingshikou Rd, Haidian District, Beijing

Curators: Dai Jinhua, Su Wei

Assistant Curator: Yang Tiange

Inside-Out Art Museum has initiated a series of work to revisit the modern and contemporary Chinese art history since the beginning of 2017. Departing from a contemporary standpoint, we look back at art history from a perspective of continuity rather than periods of ruptures, in the hope to obtain knowledge and establish a methodology to study the present. In the process, we repeatedly place contemporary art in the coordinates of culture, thought and politics—a method also used in our exhibitions and academic discussions. In our previous exhibition Crescent: Retrospectives of Zhao Wenliang and Yang Yushu, we invited Professor Dai Jinhua from the Institute of Comparative Literature and Culture, Peking University, to give a speech as part of the closing program for the exhibition, which also paved the way for the current exhibition. Inspired by the profundity of her research in films and culture, we invited Professor Dai to be our co-curator and collectively present an exhibition that focuses on various forms of cultural practice that includes visual arts.

For the Chinese society and its cultural reality at the turn of the twenty-first century, to be able to identify the mainstream value serves as the key to the understanding of Chinese culture, including its artistic representations, its shifting taste as well as its conceptual coordinates. However, there is still very little agreement concerning what mainstream value is, how many variations there exist, and what they can do. Therefore, we might have to adopt—odd may it seem—the plural form of the term, “mainstream values” in the Chinese in the Chinese context; in other words, mainstream value has to stay plural when it comes to contemporary China. These “mainstream values” are often embodied in the juxtaposition of trans-historical, cross-territorial existences of multifarious temporalities, and can appear as the amalgamation of creeds diametrically different and constantly cancel one another out.

The past three decades have seen drastic changes taking place in China. Interestingly, the role of mainstream value in this particular socio-cultural context has been one of constant exposure in the limelight, contrary to what is to be expected in a more “normative” society where the mainstream often ventriloquizes or masquerades under an invisible cloak. To evoke the mainstream value is less to establish a category or a reference point than to set up a military target—a rallying call—for resistant positions and statements. It was especially true to Chinese art and culture in the last three decades of the twentieth century. During the time, it was believed that “a demolished temple is still a temple, and a smashed idol is an idol nonetheless”. Various cultural endeavours that paradoxically ended up in embracing new gods in hoping to bidding “farewell” to the old ones have left us with blueprints—or sheer fantasies—of pantheons of many kinds. Into the 1990s, the frequent debates and the schism within the intelligentsia laid bare the significance of mainstream value being present and absent at the same time: the compartmentalization of positions corresponded to our fragmented perception of Chinese society. In other words, these divergent positions and values pointed to which global perspective and set of logic were to be adopted in the contemplation and definition of China. More significant parameters, along with multiple perspectives rooted in the local context and reaching to the world, had at once foregrounded and eclipsed the mainstream value in China.

Adding “Imagining” to “Mainstream Value” is for a reason. It does not merely reiterate the imaginary nature of mainstream value: admittedly, even the most effective system of mainstream value is still imaginary by nature. Rather, to foreground the action of “imagining” is to emphasize the imagination that has been functioning on a different plane since the turn of the new century. Confrontations with the mainstream value—perceptible within a certain range—are generally represented as tragic to a degree, yet such representations are responsible for the negligence of a few important cultural facts. Indeed, the sea change of Chinese society over the past four decades takes place not because a completely planned power structure had commanded so, yet it could not have happened had not the authority conceded to it the “elbow room”.

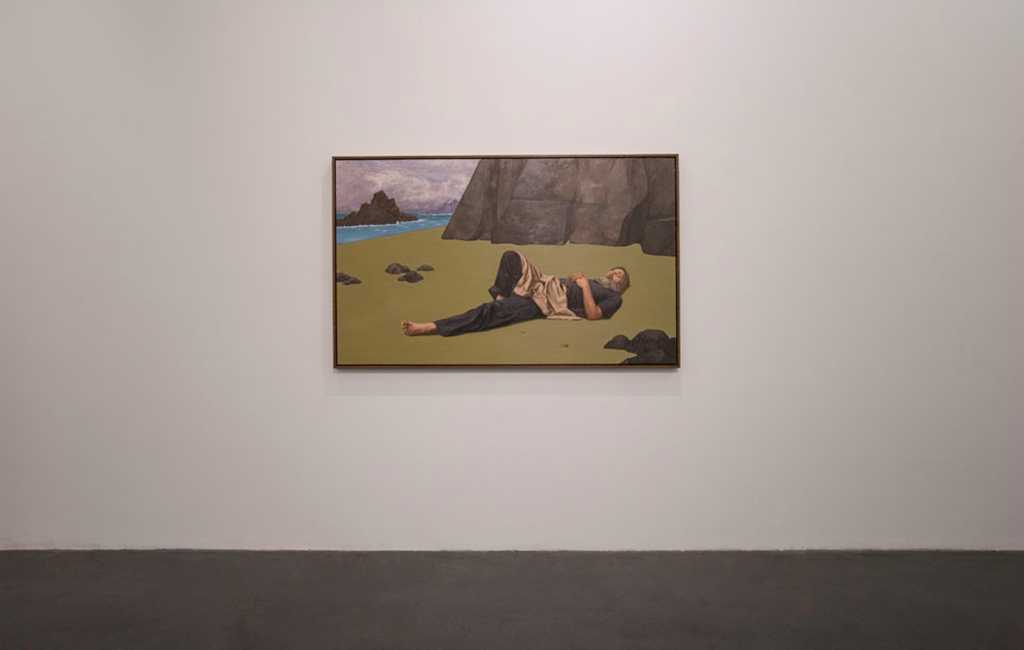

Similarly in the context of China’s art practice, the acquiesced existence of a mainstream value precedes practice that either agrees with it or goes against it. It follows that artistic practice is often divided into binary oppositions of the radical and the conservative, the contemporary and the traditional, the progressive or the unenlightened, the institutional and the non-institutional. This time, we juxtapose the so-called contemporary art with other artistic creation and productive forms in our exhibition. The latter include but not limited to theater, documentaries, films, internet culture, subcultures, literature, and debates in thought. In seven chapters of the exhibition, “Prelude: The Lonely Spirit in An Old Building”, “The Other Shore: Experimental Theatre, New Documentary and the Sixth Generation Film”, “Off the Shore: Urban Film”, “Sex/Politics: Literature”, “Divide: Intellectual History in the 1990s”, “Rear-view Mirror: Legacy and Translation”, “Condensing Lens: Reification in New Realities” and “Parallel Universes”, we look at the 1990s and the last couple of years in the new millennium. We try to provide a slice of arts through which we can observe it in terms of its position in the new period of China, its attributed values, and the efforts made by innumerable individuals. We wish to explore how the cultural and political roles shared by these creative and productive forms change, if they have abundant inner impetus and questioning, and what kind of dialogue they maintain with the authority. We raise the issue of mainstream value in arts neither because it is embarrassing or hard to prove, nor because it possesses absolute power. In fact, in contemporary art and other fields of artistic production, it is not unusual to see works and reflections that take advantage of the so-called mainstream resource and mechanism. There is also no lack of ambition or desire to create new mainstream value, nor is returning to the mainstream camp from its opposite side a rare thing. Raising the issue is not a mere exposure of our “inner shame”. We hope to outline the area where arts and authority can achieve mutual toleration in a special historical period, and within this area of mutual toleration, describe the inner impetus and critical power of arts.

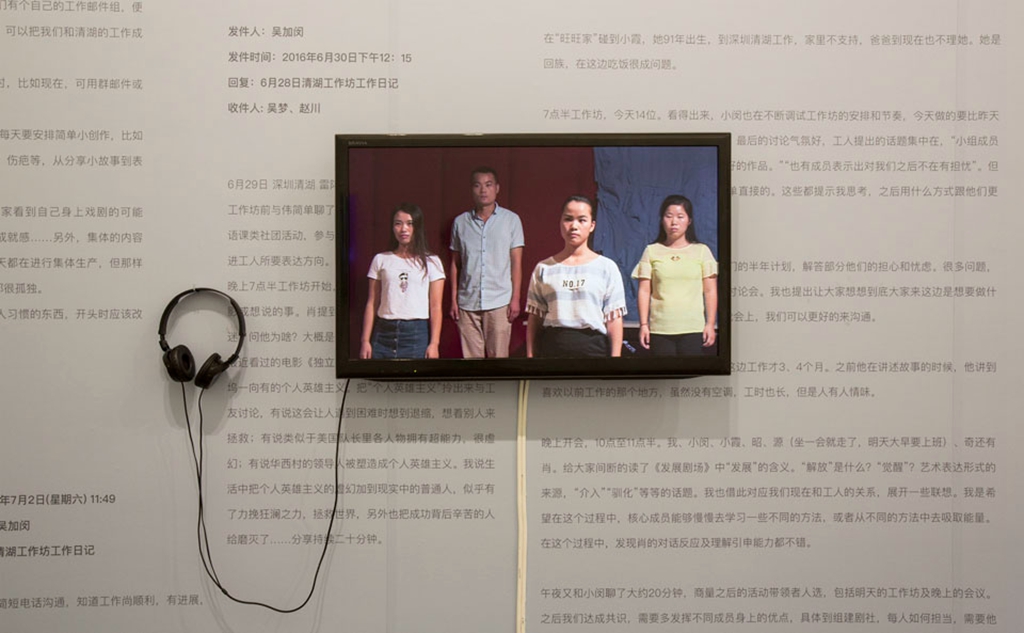

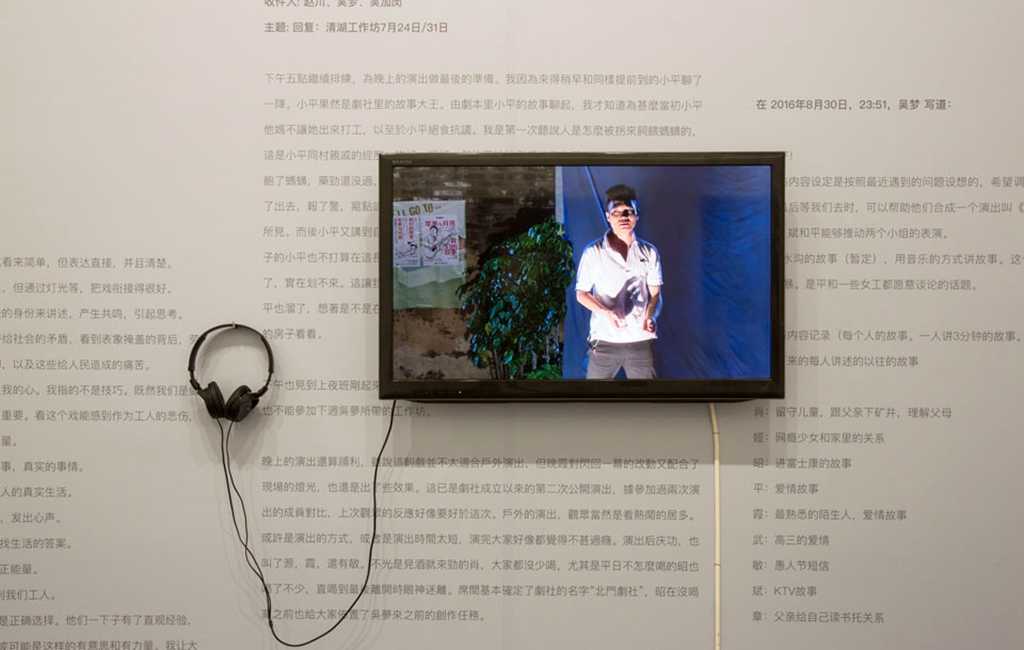

Mainstream value often leads to feelings of anger, or triggers the emergence of a new order or desires. Last year, in the middle of Beijing’s cold, somber winter, tens of thousands of people were forced out of their homes in a mass eviction. This year, in Shenzhen’s hot, humid summer, new seeds are germinating—demonstration camps are becoming diversified, crowds clarified, anxiety is surfacing, and problems are growing acute and refined. Art, along with other forms of artistic production, repeatedly collides into mainstream value at the crossroads in history, provoking power of creation and reflection.

Fu Shanchao, Liu Zhangbolong / Guang Jun / Hao Jingban / Hu Wei / Jiang Yue / Kong King-chu / Liang Ming, Mu Deyuan / Li Dafang / Li Shaohong / Li Yan / Liu Ding / Lu Wangping / Mou Sen / Mok Chiu-yu / North Gate Workers’ Theatre + Grass Stage / Ellen Pau / Wang Bing / Wu Wenguang / Xia Gang / Yan Zhou / Ye Xuan / Yu Jian / Yu Ying / Danny Yung / Zhang Jianya / Zhang Yuan / Zhao Dajun / Zhuang Hui

Walkthrough | Press