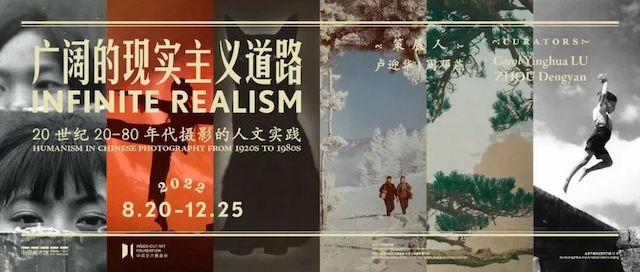

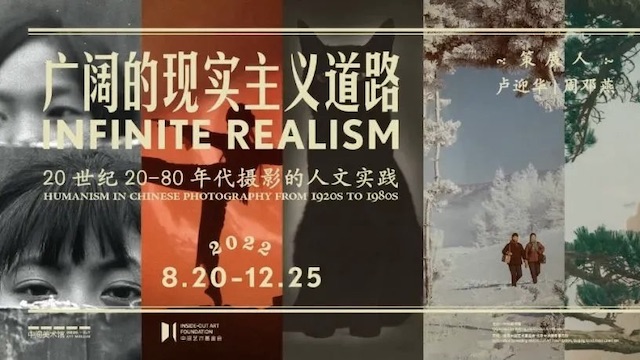

Exhibition | Infinite Realism

After intense and orderly preparations, the new exhibition Infinite Realism: Humanism in Chinese Photography from 1920s to 1980s is finally ready to open to the public on August 24!

Infinite Realism: Humanism in Chinese Photography from 1920s to 1980s

Curators: Carol Yinghua Lu, Zhou Dengyan

Exhibition Dates: Aug 20- Dec 25, 2022

Address: Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum

No.50, Xingshikou Road, Haidian District, Beijing

Foreword

Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum is pleased toannounce the opening of the new exhibition “Infinite Realism: Humanism inChinese Photography from 1920s to 1980s”. “Infinite Realism: Humanism inChinese Photography from 1920s to 1980s” displays the evolution of photographyas a creative medium in China. When photography was introduced to China in themid-1800s, it was mainly used for visual documentation and as a tool forportrait drawing. It was not until the 1920s that the artists expanded themedium’s capacity. As China faced numerous crises in the early 1900s, thepolitical movement of communism developed. Proletarian revolutionary literatureand art caused a rift in the Chinese literary and art circles. Creativesgrappled with grounding their work in reality and the experiences of ordinarypeople. With this renewed interest in reality, photographers recognized thepossibilities of the medium and began injecting humanist ideology into theirphotographs. On the one hand, the first-person camera-eye perspective of a lenscan express the subjectivity and thoughts of the artist operating it. On theother hand, photographers can document social reality, recording the turbulenceof a political moment. Because the photographic medium interacts directly withreality, photographers are also uniquely positioned to intervene in and alterreality. At the same time, artists explored the artistic, formal qualities ofphotography separate from political meaning. This interest in “art for art’ssake” rose from the liberal value of individualism was another facet of thehumanistic practice of photography.

After World War I, artists in Europe andNorth America returned to realism to express their state of mind, halting theavant-garde experimentation of the decade prior. In the 1930s, socialistrealism was introduced, upheld, and regulated by institutional guarantees andrestrictions in socialist countries. Artists and literati in socialistcountries and liberal democracies hotly debated the definition of realism. Inthe process of its policing, realism became ideological, causing many creatorsto reject the term. Socialist realism was introduced in China in the 1930s asother types of realism were accused of being subjective, and thereforebourgeois. Since then, realism has been a critical concept and method inChinese literary and artistic practice. After the 1940s, a pragmatic Chinesepolitical environment instrumentalized socialist realism to promote nationalistdogma. A rigid form of socialist realism became dominant, constraining thedevelopment of realist methods and theories.

As socialist realism became chained toideological principles and a rigid style, artists and literati have challengedthese limitations and debated the concept of realism. These debates rose out ofcreators’ resistance to conforming to the confines of a single ideology. In1956, Qin Zhaoyang wrote in “Realism – The Broad Road,” “I think the shacklesof dogmatism on literature and art are not only in China, but global. It isbecause this situation is worldwide, that it is perhaps more difficult toovercome.” Because of its close relationship with ideology, it is politicallycomplicated to interrogate how the constraints of realism generated dogmatic,formulaic works of literature and art.

In 1963, the French literary critic RogerGaraudy published the bookOn InfiniteRealism. In response to the tendency to limit realism to mechanicalmaterialism, class theory, and sociology, Garaudy declared: “A standard ofgreat realism can be drawn from the work of Stendhal and Balzac, Courbet andRepin, Tolstoy and Martin du Gard, Gorky and Mayakovsky. But what do we do ifthe work of Kafka, Saint-John Perse, or Picasso does not meet these standards?Should they be excluded from realism, from art? Or, on the contrary, should thedefinition of realism be opened up and expanded, giving realism a new dimensionby including these peculiar contemporary works, so that we can integrate allthese new contributions with the legacy of the past?” His answer was thelatter. The French writer Louis Aragon, who turned to socialist realism in the1930s, expressed his support for Garaudy in the preface to his book On Infinite Realism: “The fate ofrealism is not guaranteed once and for all, but rather depends on the valuationof new facts.” In contrast to a predefined, dogmatic realism, Aragondefended realism as a philosophy and creative approach that confronts anever-changing reality. Discarding everything that does not represent a dogmaticsense of “reality” from the category of realism is to castrate it, reducing itsgenerative potential. Rather than limiting realism to realistic forms, realismshould be understood through the more inclusive concept of authenticity. Weshould consider realism from another perspective, as a complete artisticpractice. In doing this, we can understand its ability to encompass the fulldiversity of aesthetic experiences.

“Infinite Realism: Humanism in ChinesePhotography from 1920s to 1980s” showcases the emergence of alternative realistpractices in Chinese photography. The works in this exhibition break the formalrule that realism must appear “realistic.” They transcend the modernistdichotomy between art and reality and refute a simple equation between realismand reality. The photographs on view bring humanistic awareness into dialoguewith history and reality. The works express photographers’ individual,penetrative gazes on reality, as well as their multi-layered photographicinterpretations. The exhibition presents a broad picture of realist practices.In this picture, human beings—as observers, recorders, and photographicsubjects—as well as ideological motives and the photographic content, are atthe core of consideration and manifestation.

“Infinite Realism: Humanism in ChinesePhotography from 1920s to 1980s” is the latest exhibition to research and presentthe history of Chinese contemporary art by Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum. Theexhibition presents more than 400 photographic works and nearly 100 documentsby 150 plusphotographers (including anonymous ones) over the course ofsix decades, including many important works and rare documents that are beingexhibited for the first time. The exhibition describes and presents thephotographic practices of different historical periods in five sub-topics:”Flowers under the Roof of Realism”, “Multiple Facets of WartimeRealism”, “Socialist Realism and Realism”, “The Mirage ofRealism”, and “Realism and People in the Reality”. Theexhibition is co-curated by Carol Yinghua Lu, director of Beijing Inside-OutArt Museum, and Zhou Dengyan, a photography historian from Beijing FilmAcademy. The exhibition is made possible by the generous support of manyphotographic artists, their families, scholars, collectors and researchinstitutions, for which we would like to express our sincere gratitude. Duringthe exhibition period, we will organize a series of academic and publiceducation events during the course of the exhibition, please stay tuned to ourWeChat public number.

Participating Artists

(In alphabetical order)

An Ge, Ao Enhong, Bai Tao, Bao Kun, Bei Dao, Bi Jianfeng, Chen Baosheng, Chen Bo, Chen Fuli, Chen Shuxia, Da Hai, Dai Zenghe, Dang Quanli, Deng Wei, Du Zhizhong, Fan Huichen, Fang Dazeng, Gu Cheng, Gu Zheng, Guo Song, Hei Ming, Hong Hao, Hou Dengke, Hu Wugong, Huang Cheng, Huang Daoming, Huang Lin, Huang Xiang, Huang Yongyu, Jia Chaozheng, Jiang Bingnan, Jiang Guoliang, Jiao Jingquan, Jin Bohong, Jin Shisheng, Lang Qi, Li Feng, Li Guohua, Li Jilu, Li Ming, Li Shaotong, Li Shengli, Li Tian, Li Xiaobin, Jia Tiansheng, Liang Zude, Ling Fei, Liu Bannong, Liu Feng, Liu Guangcheng, Liu Jie, Liu Qinghe, Liu Xucang, Lu Shifu, Lv Xiaozhong, Luo Bonian, Ma Mingjun, Ma Yuhuan, Mao Zhanping, Meng Zhaorui, Pan Ke, Peng Kuang, Qi Guanshan, Qian Qun, Ren Shulin, Sha Fei, Shao Du, Shao Jiaye, Shi Baoxiu, Shi Shaohua, Shi Zhimin, Song Shijing, Sun Zhenjie, Shen Xun, Wang Hu, Wang Jinfu, Wang Junhua, Wang Miao, Wang Ping, Wang Ruihua, Wang Xiang, Wang Xiebai, Wang Yan, Wang Yin, Wang Youshen, Wang Yuejin, Wang Zhiwen, Wang Zhiting, Wang Zhiping, Wei Dezhong, Wei Shouzhong, Wen Danqing, Wu Wenhao, Wu Yinbo, Wu Yinxian, Wu Zhongxing, Wu Zuzheng, Xia Yonglie, Xu Xiaobing, Xu Yingzhe, Xu Youhui, Xu Qi, Xu Zhuo, Xue Zijiang, Yang Qun, Ye Liuru, You Yungu, Yu Bangyan, Yuan Shande, Yuan Yiping, Zhai Chunlai, Zhang Aiping, Zhang Baoan, Zhang Jingli, Zhang Li, Zhang Yinquan, Zhang Yunlei, Zhao Jiexuan, Zheng Jingkang, Zheng Jun, Zhou Chunyan, Zhou Wannian, Zhu Lihe, Zhu Tianmin, Zhu Weiping, Zhuang Xueben

Curators

Carol Yinghua LU is an art historian and a curator. She received her Phd degree in art history from the University of Melbourne in 2020. She is the director of Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum. She was the artistic director and senior curator of OCAT, Shenzhen (2012-2015), guest curator at Museion, Bolzano (2013) and the China researcher for Asia Art Archive (2005-2007). She was a recipient of the ARIAH (Association of Research Institute in Art History) East Asia Fellowship (2017), Yishu Awards for Critical Writing and Curating on Contemporary Chinese Art (2016) and visiting fellow in the Asia-Pacific Fellowship Program at the Tate Research Centre (2013). She was the co-artistic director of Gwangju Biennale and the Shenzhen Sculpture Biennale (2012).

She has acted as a jury member for Hyundai Blue Prize Art + Tech (2022, 2021), Tokyo Contemporary Art Award (2022-2019), The Choi Foundation Prize for Contemporary Art (2022, 2021), Gallery Weekend Beijing Prize for Best Exhibition (2022, 2020-2017), Han Nefkens Foundation – Loop Barcelona Video Art Award Production (2021, 2020), abC Art Book Award (2021), Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative (2019), Hugo Boss Asia (2019), International Award for Art Criticism (2014), the Future Generation Art Prize (2012), and the Golden Lion Award at Venice Biennale (2011).

ZHOU Dengyan is an art historian with a research focus on photography in China. She holds a PhD in Art History from Binghamton University. She is the editor of Images of China 20th Century Chinese Photographers – Shi Shaohua (2019) and The National Photographic Art Exhibition Office: Reminiscences and Documentary Materials 1972–1978 (2015). Her recent studies have been published in Literature & Art Studies, Theory and Criticism of Literature and Art, Chinese Journal of Art Studies, Contemporary Cinema, Trans Asia Photography Review, photographies and OSMOS. She is currently teaching at Beijing Film Academy.

We would like to thank the following family members of photographers, scholars, collectors and research collections for their generous support

(In alphabetical order)

Cai Tao, Chen Shen, Chen Wei, Chen Xiaoli, China Image Gallery, Hou Bingzhi, Hou Xiaojin, Intergallery, Jin Hua, Jin Youming, Li Xiaoyu, Liu Lanlan, Li Shu, Luo Yifei, Na Risong, Niu Jie, Qing Lan, Qi Yan, Rong Rong, Shao Dalang, Shenzhen Yuezhong Museum of Historical Images, Tang Dongping, Three Shadows Photography Art Centre, Wang Yiqiang, Wu Wei, Xue Baogen, Yang Xilong, Zhai Linfeng, Zhang Xiaoai, Zeng Huang, Zhuang Jun

翻译:Ariana Chaivaranon 陈蕊

平面设计:luomantic

编辑排版:易若扬

Leave a Reply